Security starts at design time

During the agent design process, think through:- What capabilities does this agent need?

- What data does it need access to?

- Who will it communicate with?

- What could go wrong, and how bad would it be?

Agent Design Canvas

A structured framework for designing agents that actually work—including security considerations.

Agent Design Training

Courses on designing, building, and securing effective AI agents.

The intern metaphor

Agent design can be compared to hiring a new intern. Does the intern need access to the company bank account? Probably not. Most jobs don’t require it, and removing that access entirely eliminates a whole category of risk. What if they need access to customer data AND email? Now you have a potential leak vector. The intern could accidentally (or be manipulated into) sharing sensitive information externally. You need to think about:- Do they really need both? Can you separate the tasks so one role has data access and another handles email?

- If yes, what safeguards? Maybe require approval for external emails. Maybe restrict email to specific domains. Maybe monitor closely at first.

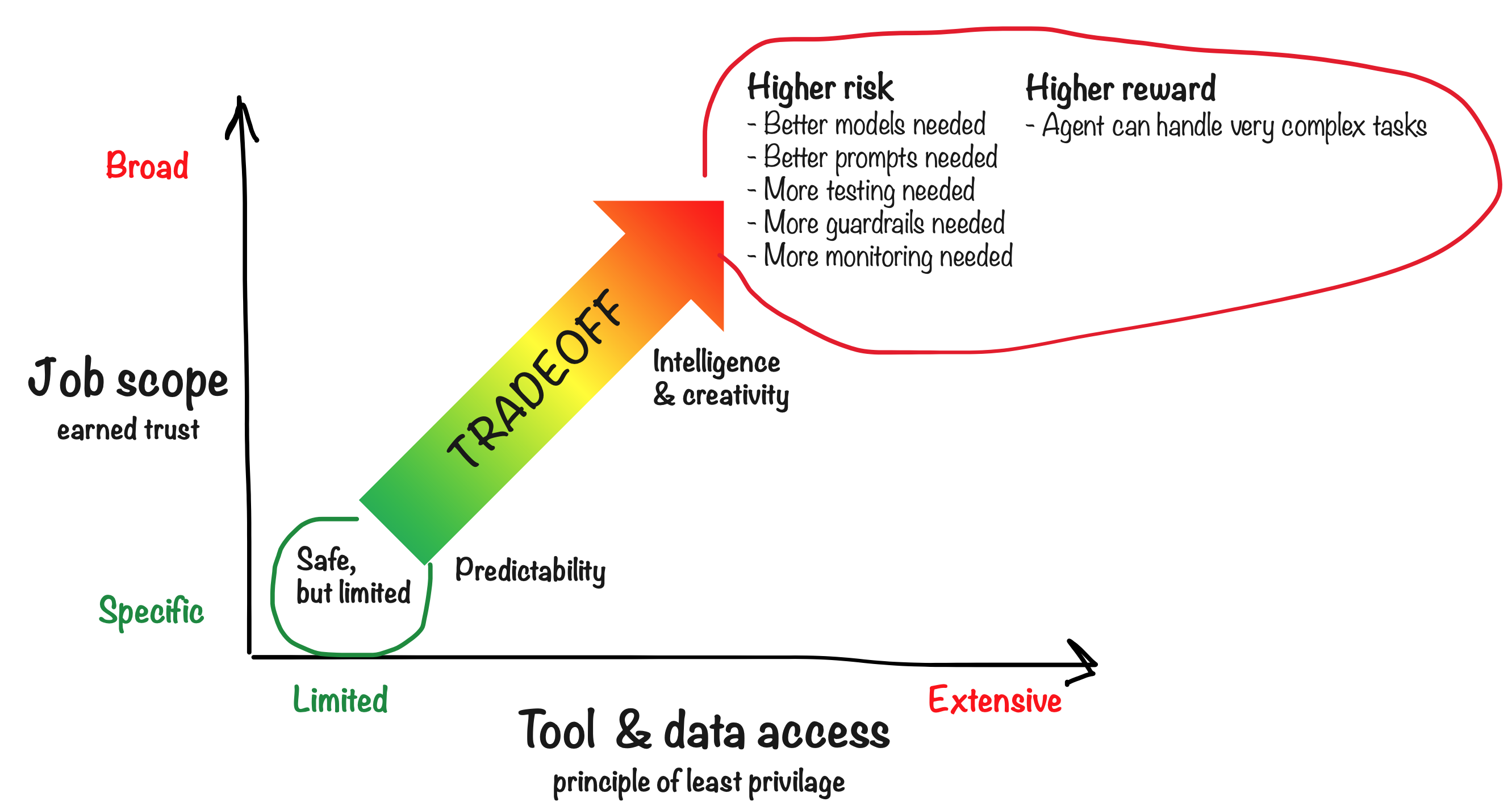

Risk vs Reward

| Factor | Lower Risk | Higher Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Specific, narrow task | Broad responsibilities |

| Tools | Read-only access | Write, send, call, delete |

| Communication | Internal team only | Customer-facing, public |

| Data access | Public information | Confidential, PII, financial |

| Reversibility | Easy to undo | Permanent or hard to reverse |

Examples across the spectrum

Low-risk: Ticket priority agent

Imagine an agent whose only job is to set the priority field on incoming support tickets. That’s it—no email, no customer data, no external communication. Just read the ticket and set a priority. What’s the worst that can happen? A ticket gets the wrong priority. Not the end of the world. This agent is safe essentially out of the box, just by nature of its limited scope and tools. Minimal guardrails needed.High-risk: Customer inquiry handler

Now imagine an agent that handles incoming customer inquiries. It has access to public-facing email, a database with customer information, and can reach out to people and make decisions with real impact. This could be a VERY valuable agent—but it takes more work to make it safe:- Better models — Use the best available (usually also the most expensive)

- Better instructions — Spend more time crafting and iterating on clear guidelines

- More testing — Test edge cases and adversarial scenarios thoroughly

- Guardrails — Code-enforced constraints like whitelists that can’t be bypassed

- Human-in-the-loop — Require approval for important decisions

- More monitoring — Watch closely, especially early on

- Gradual autonomy — Start with limited scope (like a trainee), expand as it proves itself

The reality: Most agents are in between

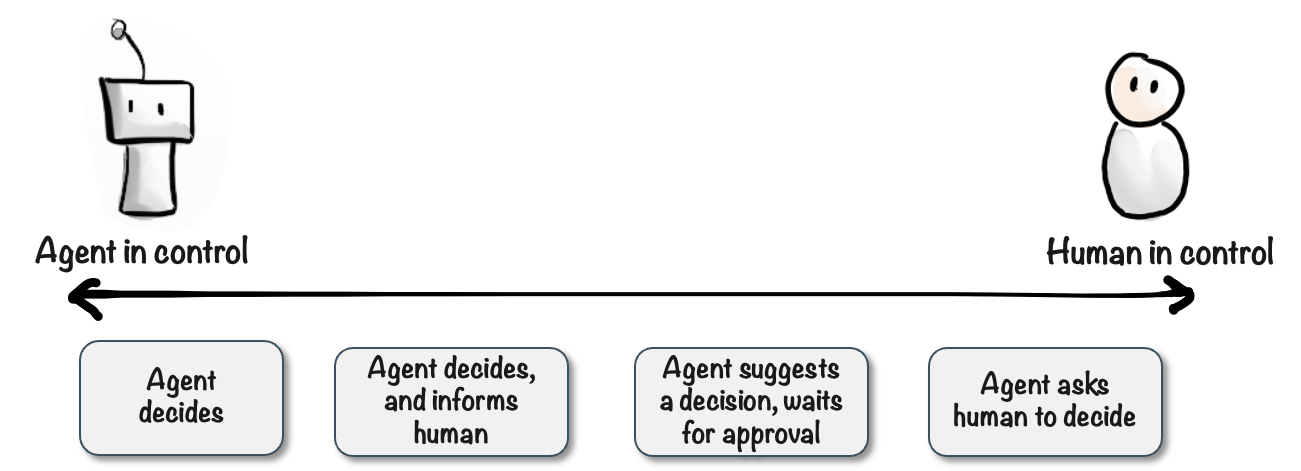

Most agents fall somewhere between these extremes. The most crucial decisions are usually best left to humans, while the agent handles the grunt work—the boring, repetitive tasks—and provides data and insights the human can use.Who decides?

A crucial part of agent design is deciding who makes decisions—the agent or the human. This is a spectrum:

| Mode | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Agent decides | Low-stakes, reversible actions where speed matters | Setting ticket priority |

| Agent decides, informs human | Medium-stakes actions where visibility is important | Sending internal status updates |

| Agent suggests, waits for approval | Higher-stakes decisions where human judgment adds value | Issuing a customer refund |

| Agent asks human to decide | Critical decisions, edge cases, ambiguous situations | Escalating a complaint to leadership |

Guiding principles

- Principle of Least Privilege — Give agents only the capabilities and data they need for their job—no more. An agent that doesn’t have email access can’t accidentally send a bad email.

- Principle of Earned Trust — Start narrow and expand as the agent proves itself. Begin with approval requirements, then relax them once you’re confident in the agent’s behavior.

Advanced agents with broad scope CAN be safe—it just requires more careful design and ongoing attention. Don’t be afraid of powerful agents; be thoughtful about how you build them.