Before designing an agent, make sure you’ve identified a suitable use case. See Find Your Use Case for guidance.

Simple vs complex agents

For simple agents, you don’t need much of a design process. Just create an agent and tell it what to do:“Do a competitor analysis every Monday morning and send me a report.”Provide some basic context, iterate on the report format, and you’re done. This conversational approach works well for personal assistants and straightforward automations. But for more complex agents—especially those that handle external communication, work with sensitive data, or fit into team workflows—a structured approach pays off. You’ll save time by thinking things through before building.

The Agent Design Canvas

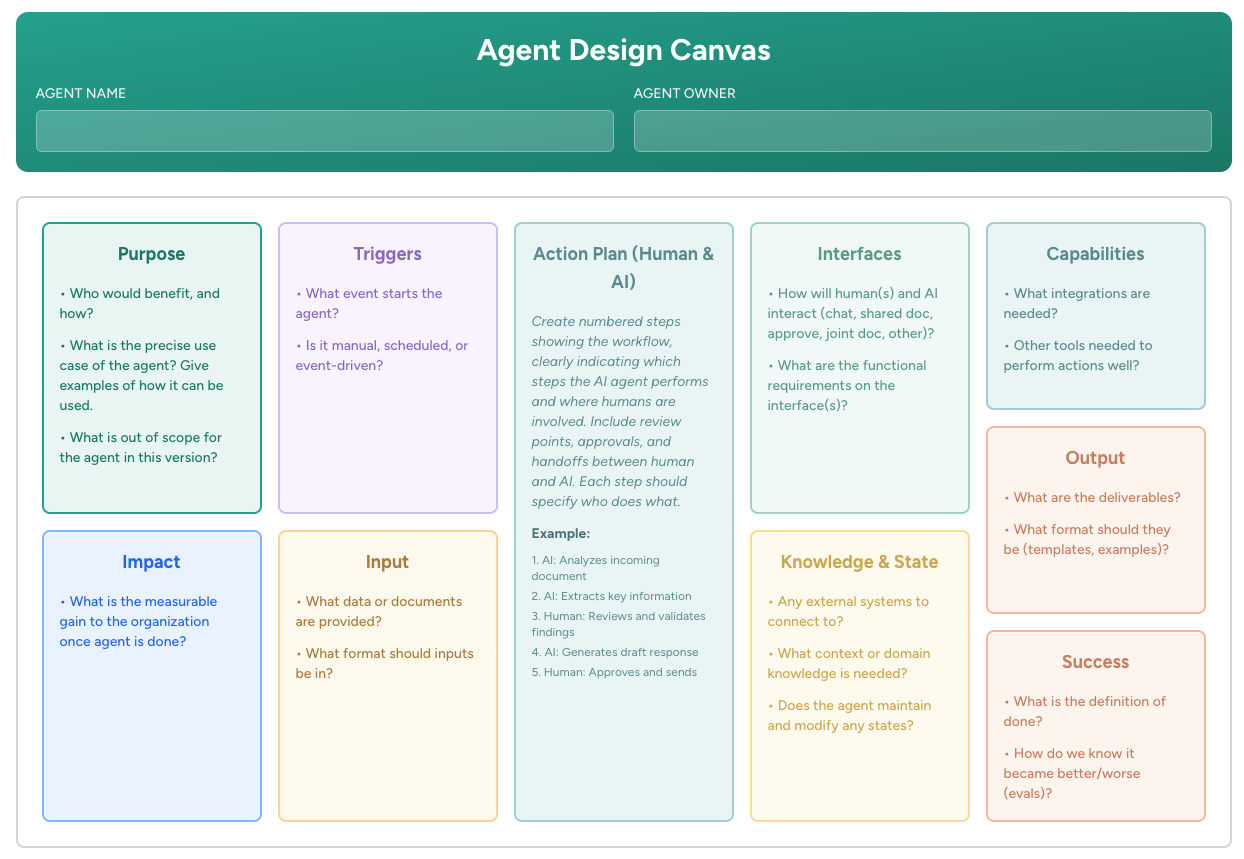

We’ve evolved the Agent Design Canvas as a tool to guide the design process. It’s a framework for thinking through all the critical aspects of agent design before you start building.

Get the Canvas

Download the PDF or use the interactive online version

Canvas Deep Dive

Read Leilei’s blog post “The AI Agent Design Canvas: How We Design AI Agents That Actually Work”

How to use it

The boxes are there to raise questions in your mind—you don’t need to strictly fill in each one. Skip boxes that feel irrelevant. Add boxes that are missing for your context. For example, a security-sensitive agent might need a “What could go wrong?” box for risks and mitigation strategies. Some teams keep the canvas alive as a living document that evolves with the agent. Others use it only for bootstrapping, then set it aside once the agent is running (or keep it as a record of the original design). Either approach is fine. The canvas is just a tool.The ten aspects of agent design

Let’s walk through each section of the canvas. For each aspect, we’ll explain the key questions and show an example from a Manuscript Screening Agent that helps a publishing team filter incoming submissions.Purpose

The foundation of everything. Get specific about what problem you’re solving and who benefits. Key questions:- Who would benefit, and how?

- What is the precise use case? (Give examples)

- What is out of scope for this version?

Manuscript Screener: Editorial team saves time by focusing only on high-quality submissions. The agent screens incoming manuscripts to the public submission inbox. Out of scope: filtering among the high-quality submissions (humans do that).

Triggers

What wakes the agent up? Every agent needs an activation mechanism. Key questions:- What event starts the agent?

- Is it manual, scheduled, or event-driven?

| Trigger type | Example |

|---|---|

| Manual | User sends a chat message |

| Scheduled | Every Monday at 9am |

| Event-driven | Incoming email, webhook, calendar event |

Manuscript Screener: Triggered by incoming email from the public manuscript submission address.

Action plan (human & AI)

This is the heart of the design. Create numbered steps showing the workflow, clearly indicating which steps the AI performs and where humans are involved. What are the specific steps? Who does what—agent or human? Where are the handoffs, review points, and approvals?Manuscript Screener:

- Agent: Receives email with manuscript and reads the cover letter and first 5 pages

- Agent: Reviews content quality and sets a score (yes/maybe/no)

- Agent: Summarizes the recommendation with reasoning and emails it to the human

- Human: Reviews the assessment and takes the best manuscripts for further review

The most common design oversight is not thinking through human-AI handoffs. This leads to agents that work in theory but don’t fit actual workflows.

Interfaces

How do humans and the agent interact? The interface choice can determine whether an agent actually gets used. How will humans and AI interact? Chat, email, Slack, shared documents, approval widgets? What are the functional requirements on the interface?Manuscript Screener: Email only. Human receives reports via email from the agent. No other interface needed.

Capabilities

What tools and integrations does the agent need to do its job? What integrations are needed? What other tools are required? Apply the principle of least privilege: give agents only the capabilities they need—no more. An agent without email access can’t accidentally send a bad email.Manuscript Screener: Receive email, send email, access/read documents.

Impact

Define success in business terms. This helps you evaluate whether the agent is worth building and provides a metric for ongoing improvement. What is the measurable gain to the organization once the agent is working?Manuscript Screener: Screening efficiency increased by 80%, allowing the editorial team to focus on high-quality manuscripts.

Input

What data or documents does the agent receive? This is the part of the agent’s context that varies with each run. What data or documents are provided? What format should inputs be in?Manuscript Screener: Each incoming email includes the email body, plus a manuscript and cover letter as attachments.

Knowledge & state

What background information and external connections does the agent need? Any external systems to connect to? What context or domain knowledge is needed? Does the agent maintain and modify any state?Manuscript Screener: Agent needs examples of what “great,” “just-good-enough,” and “not-really-good-enough” levels of quality look like.

Output

What does the agent deliver? Be specific about format and destination. What are the deliverables? What format should they be in? Consider using templates or examples.Manuscript Screener: Agent’s review of incoming manuscripts is aligned with how the human user would evaluate them.

Success

How do you know the agent is working? Define both immediate success and ongoing evaluation. What is the definition of done? How do you know if the agent became better or worse over time?Manuscript Screener: Agent reviews 100% of incoming submissions within 24 hours and provides consistent scoring. Target pass rate: ~40%.

Prototype early

The canvas is useful, but don’t spend too long thinking before you actually try something. Build a minimum version of the agent directly in the platform—even if you have to fake things.- Fake data: If you don’t have access to real data yet, use fake data. You can even ask the agent to generate realistic test data for you.

- Fake integrations: Ask the agent to simulate connections to systems you don’t have access to yet. “Pretend you received this email and tell me what you would do.”

- Quick integrations: Use the HTTP capability to test various API integrations before committing to a full setup.

The agent owner

In a team context, every agent needs a clearly defined owner—think of them as the agent’s “boss.” An agent may interact with many people, and those people will have feedback and ideas for improvement. But it’s usually best for one person (or an owner pair) to be responsible for the agent’s behavior. They tweak the instructions, they follow up when something goes wrong, they decide when to expand or change the agent’s role. Without a defined owner, you risk one of two failure modes:- Nobody improves the agent — Issues pile up, the agent drifts, and eventually it stops being useful

- Everybody improves the agent — Like an intern with no clear boss, receiving conflicting instructions from multiple people, the poor agent becomes confused and unreliable

Using the canvas in practice

For team workshops: Get everyone in the same room, work through the canvas together, and reach alignment before building. This can take 1–4 hours depending on complexity, but saves days of misalignment later. For solo design: Use it as a checklist to ensure you’ve thought through all aspects before implementation. For complex agents: Any section of the canvas could mean significant time figuring out the right solution. That’s normal—better to discover complexity during design than during building.Common pitfalls the canvas prevents

| Pitfall | What goes wrong | How the canvas helps |

|---|---|---|

| Unclear purpose | Everyone has a slightly different understanding | Forces alignment on specific purpose before building |

| Context overload | Too much information makes the agent confused | Pushes you to think critically about what’s actually necessary |

| Undefined success | Teams either over-engineer or ship something that doesn’t work | Ensures everyone agrees on what “done” means |

| Ignored handoffs | Agent works in theory but doesn’t fit workflows | Explicitly maps human-AI collaboration points |

Keeping instructions clean

One common mistake is dumping everything you can think of into the agent’s context. This creates a low signal-to-noise ratio, leading to confused agents and low-quality output. Limit context to what the agent actually needs—remove anything that’s just “good to know.” During the creation process, it’s OK and normal for instructions to get a bit messy as you iterate. But then clean them up: simplify, clarify, remove redundancy. The agent can help with this—ask it to review its own instructions and suggest improvements. Don’t worry about breaking things when you simplify. Instructions are version controlled—if you ask the agent to clean up and the results aren’t what you wanted, you can always roll back to a previous version.Iteration is essential

AI agents need human feedback to become good. They improve through iteration and guidance—more like new team members who need coaching than software that just runs. This is why the best agent creators are often the actual users, not IT departments. Only the user knows when things change, when performance has drifted, or when new requirements emerge.Getting an agent from “works pretty OK” to “this is awesome” usually takes a few rounds of refinement. Start with 80-90% as your target—the last 10% often takes more effort than it’s worth.

FAQ

Do I need to fill out the entire canvas?

Do I need to fill out the entire canvas?

Not always. For simple agents, you might only need to think through Purpose, Triggers, and Capabilities. The canvas is a tool, not a bureaucratic requirement. Use the parts that help.

How long should the design process take?

How long should the design process take?

For a simple agent: 15–30 minutes of thinking, then iterate as you build.For a complex agent with team alignment needed: 1–4 hours of workshop time, followed by iterative refinement during building.

What if requirements change after I've designed the agent?

What if requirements change after I've designed the agent?

That’s normal. Agent design is iterative. Update the canvas as you learn, and adjust the agent accordingly. The canvas is a living document, not a contract.

Should I design the agent before or after creating it in the platform?

Should I design the agent before or after creating it in the platform?

For complex agents, design first—at least the Purpose, Action Plan, and Success criteria. For simple agents, you can create and design simultaneously through conversation with the agent.